What ordinary Libyans’ justice journeys teach us about access to justice

To learn about access to justice, it is essential to research empirically what ordinary people do with 'potentially legal problems': their justice journeys.

Tolstoy famously opened the novel Anna Karenina with, ‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ Similarly, while law categorizes a society’s troubles into a digestible number of comparable transgressions, the first phase of our research ‘Access to Justice in Libya’ has taught us just how diverse injustices and subsequent efforts to search for justice are. Our report ‘The Long and Winding Road: Justice seeking and access to justice in Libya’ (2022) attempts to distill from all these families’ unique suffering more general patterns. We believe that recommendations for better policies and laws ought to be informed by such an empirical analysis of what people actually do with their (potentially) legal problems.

For a year (September 2021 - October 2022) twelve researchers in different parts of Libya – Tripoli, Bani Walid, Sabha, Ubari, Benghazi, Al Marj, Tobruk, and the oasis areas of Jalu, Jakharrah, and Awjilah (see map) – researched one particular type of injustice (e.g., domestic violence, dispossession, disinheritance, pollution, murder) through the experiences of a handful of individuals. Through qualitative research with these ‘justice seekers’ and other key actors (e.g., police, lawyers), they studied the ‘justice journeys’ that people travelled. Dr Jazia Shayteer, for instance, wanted to understand how women in Benghazi respond to marital violence, and so she studied the ‘justice journeys’ of five women; Azza, Khadija, Khawla, Rima, and Fatima.

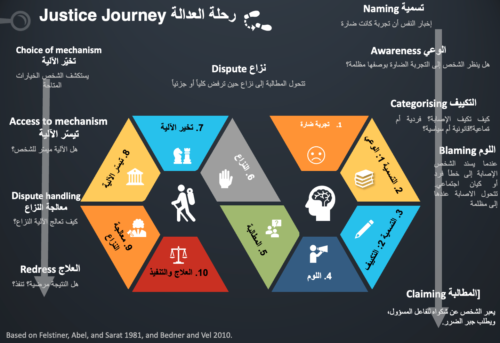

Based on two earlier analytical frameworks on disputing (Felstiner et al 1981) and access to justice (Bedner and Vel 2011), and discussions about our own findings, we drafted an analytical framework (see below image). Crucially, every journey is different, and this framework does not always fit. But it proved helpful to ask disputants about the different steps or stages of their dispute, and the obstacles and opportunities they met along the way.

The analysis of these micro-level disputing practices has yielded a lot of insights. The twelve case studies (see image) drew specific conclusions, from which 'The Long and Winding Road' distilled 25 general observations which we will study further in the rest of this research project.

Libyans’ experiences of injustice often have two components: the original ‘injurious experience’ and the subsequent, invariably hard, long, and painful ‘justice journey’. Institutions often required certain evidence – documentation of citizenship, of land ownership, proof of pollution, forensic reports – which was difficult to secure due to conflict, state weakness, or the lack of technical expertise. For example, Ms Khadiga Farag found that oasis inhabitants had no access to an independent facility to test if water and soil had indeed been contaminated by oil production, and they distrusted the experts of the National Oil Corporation and the oil companies. Even when claimants reached a favourable ruling or remedy, those were invariably partial and often remained unenforced. This was the case in Dr Suliman Ibrahim’s study of a land dispute in Tobruk, where a compensation committee ruled that the protagonist ought to get his land back and all attempts at implementation failed.

This left many ordinary Libyans disillusioned, hopeless, and angry. Many Libyans simply put up with even the most serious injustices (i.e., the disappearance or murder of a loved one) out of fear, trauma, or simply low expectations that anything good will come from searching justice. Justice in Libya was rarely blind. Often, the disputants’ ‘social weight’ (thaqal ijtima’ai), personal connections (wastah), or political allegiance (‘revolutionaries’ vs ‘Gaddafi loyalists’) facilitated or obstructed their access to forums and the outcome they received. Sometimes, the politicisation of justice makes judges reluctant to rule – like Mr Ali Abu Raas found in the cases of relatives of people murdered in the Abu Salim-massacre. On the upside, we found that Libyans were often adept at forming alliances or ‘victims associations’ to strengthen their position; these played a role in seven out of twelve case studies.

Given the staggering injustices and troubled justice journeys, perhaps it is surprising that many Libyans continue to take their disputes to local authorities – be they police, prosecutors, courts, municipal councils or community-based institutions like tribal leaders (shuyu¯kh al-qaba¯’il), wise men’s councils (majalis al huqama), and customary committees (lijan urfia). Disputants often used all the mechanisms remotely at their disposal – with the disputants in Dr Suliman Ibrahim’s study involving fourteen authorities. Disputants were rarely discouraged by formally-limited jurisdictions and often pursued several processes – formal and informal – simultaneously.

The second phase of our research (November 2022 - November 2023) focuses in a similarly empirical manner on twelve such Libyan ‘justice providers’ and their role in providing access to justice.